Intel Custom Foundry Was Killed Already, Can the Fabs Rise Again?

Intel operated its custom foundry business for eight years before folding in 2018. What makes Intel think it can succeed a second time with Intel Foundry Services?

Meet the Competition

"But [Intel Custom Foundry] is a very serious competitor to our customers. That really I would say applies even greater pressure on us than Intel as a direct foundry competitor."

Those are the words of Morris Chang, PhD., founder and CEO of silicon behemoth TSMC. He was describing the potential of Intel poaching TSMC customers to switch to Intel's own Custom Foundry (ICF) business.

But Chang was not praising Intel. In fact, this was a clever jab at one of the core problems of Intel's Custom Foundry business model. Instead, he was highlighting the inherent conflict of interest Intel faced between its core offerings and its custom foundry side project.

You see, Intel's primary business is based around designing, fabricating, and marketing its own high-end microprocessors. In doing so, it is in competition with other companies who design chips, including those who do not operate their own fabs. Think Nvidia, Qualcomm, and Apple - all of whom are major customers of TSMC.

Intel operating its Custom Foundry on the side was awkward. There could only ever be an inherent conflict between themselves and the customers they wished to attract.

This conflict would become the defining problem of Intel's first attempt at a foundry business.

The Story of Intel Custom Foundry

With the market failure of the Ultrabook generation and general resentment of the launch of Windows 8, Intel was not in a good place. PC sales were declining in 2013, which meant the chip giant was selling fewer chips. Something was needed to invigorate new business.

By this point, Intel had already been doing small-scale work in its chip fabrication plants for small third-party firms like Tabula and Achronix Semiconductor. In doing so, Intel set a limiting policy for itself. It would only consider manufacturing for specific customers - ones that were not in direct competition with Intel itself.

But Intel wanted to grow this side of the business. It was well understood that Fabs-as-a-Service could be a lucrative offering, as evidenced by the success of TSMC. And in recent times, building new semiconductor fabs had become increasingly difficult to pay for. The writing was on the wall that the PC market would not be able to justify the increasing costs of chip production.

And so, Intel decided to target the FPGA field as a set of potential new customers. The FPGA market was large enough to be interesting to Intel as a business, but it was not the type of product that would compete with Intel's own product portfolio, i.e., the CPU market.

"There's no doubt in my mind the foundry will be a significant player in the future."

That confidence is from Sunit Rikhi, General Manager of Intel's Custom Foundry division, on the idea of expanding Intel's custom chip fabrication capabilities to more customers.

Rikhi would become a very strong proponent of ICF. He was the internal champion behind the division, creating a very necessary bridge between the outside world and Intel's internal fortress. He made sure customers, even the small ones like Tabula and Achronix, could have an impact on the Intel foundry technology.

At the time, Altera and Xilinx were the two largest competitors in the FPGA market. Both companies were constantly seeking out any form of technical advantage.

Xilinx had been fabbing their chips through United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), and Altera had been a customer of TSMC. But in 2010, Xilinx had announced plans to move their fabrication to TSMC as well. Altera would need a new competitive advantage and saw Intel Custom Foundry as an opportunity.

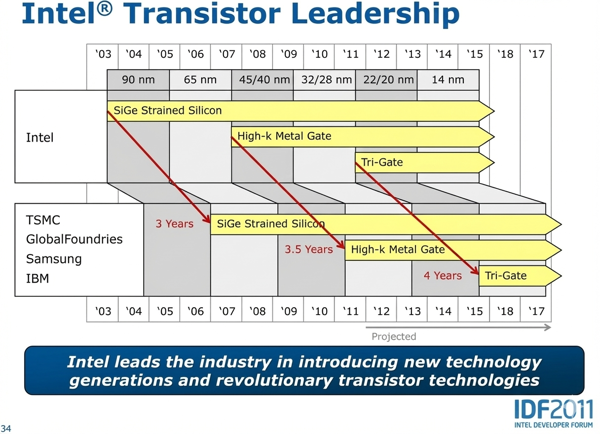

In February 2013, Intel struck a deal with Altera in an agreement to start manufacturing their programmable chips. This would be the first large-scale manufacturing deal for ICF. Altera's products were to be based on Intel's highly competitive 14nm process node, giving them a full generation of advantage over competitor chips being manufactured by TSMC.

Intel Custom Foundry would pride itself with over 10 major customers on its books. The division was pulling in around $1 billion in recurring revenue, something any business unit could be proud of.

Internal Conflicts Inside

While the chips produced at Intel were commendable, the company culture behind them was anything but.

Inside the walls of Intel Technology Group (ITG) - the division responsible for progressing manufacturing technology - ICF was seen as a nuisance, even problematic. ITG was focused on one thing: making Intel chips better. The ICF wasn't making Intel chips; they were making chips for third-party customers, some of whom could potentially compete with Intel.

There was an unavoidable clash forming.

Former customers of TSMC were used to white-glove treatment. The Taiwanese manufacturer provided deep insight into node development for each of their customers. Design and development was done with regular feedback from the companies designing products for TSMC fabs.

But Intel's R&D team kept things secret. They absolutely refused to divulge process node details.

On top of the secrecy, ITG resisted making any changes to accommodate ICF customers. The top priority for ITG was optimizing for Intel's own chips, and everyone else took a backseat.

The power imbalance between ITG and ICF was untenable. Intel Custom Foundry may have been generating around a billion dollars in revenue, but this was a drop in the bucket to Intel. The scrappy division lacked the gravity needed to force changes. When push came to shove, ITG prioritized the internal roadmap, and customer feedback from the foundry division went nowhere.

The Downfall of Intel Custom Foundry

If internal politics had been cracking the foundation of ICF, then the infamous 10nm delays at ITG were like finding out the pipes were made of lead coated with asbestos. Originally due in 2016, Intel's 10nm node would be delayed again and again. And again. And again.

Reliability is the currency of the foundry business, and as the 10nm delays mounted, the pipeline of customers dried up.

The 10nm delays would lead to the greatest ICF disappointment of all—the inability to capture Apple as a customer.

It was hardly a secret that Intel was targeting Apple for the iPhone's A9 chip. But Apple was interested in Intel's upcoming 10nm node, not the existing node at 14nm. After several in-person meetings, the deal finally fell through. Tim Cook reportedly said to TSMC's Morris Chang that, "Intel is not good at contract manufacturing."

In what would later prove to be a total miscalculation, Intel decided to acquire FPGA maker Altera in 2015 - one of Intel's largest, premier foundry customers. This sent a shock through the rest of the FPGA market, as Intel's potential customers realized their fabrication partner was now their primary competitor. Intel had just declared they were willing to compete with their own customers.

Soon after, Rikhi was replaced by leadership that prioritized the goals and mission of ITG. In doing so, they eliminated the one and only strong internal advocate for external customers. It was decided that only Intel chips mattered.

And by 2018, the Intel Custom Foundry experiment was over. The business unit was dissolved, and its remaining customers were routed directly to the Intel Technology Group.

Plans for IDM 2.0

Fast forward to 2021. Pat Gelsinger, newly minted Intel CEO, announced his plans for IDM 2.0 (short for Integrated Device Manufacturer). At the center of his plan was Intel Foundry Services (IFS), a supposedly distinct, standalone business unit.

Unlike ICF, the offerings of IFS were even sweeter. Intel would take care of all parts of manufacturing, packaging, and process technology, and would even allow third parties to make use of Intel's x86 intellectual property.

To back this up, Intel announced a massive buildout in New Albany, Ohio, for a megafab site costing over $20 billion. The goal was to explicitly position Intel as a Full Service Foundry.

So what happened?

Execution Meets Reality

Pat Gelsinger was ousted as CEO in December 2024.

The road to redemption has been fraught with problems. The financial reality at Intel became grim. Intel announced $3 billion in cost reductions, slashed employee pay, suspended bonuses, and cut retirement matching.

In November 2024, after 25 years of being a member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, Intel was dropped from the premier index, only to be replaced by Nvidia. The company announced plans to lay off an additional 24,000 employees and to scrap billions in planned European infrastructure investments.

Lip Bu Tan was brought in as the new Intel CEO in March 2025 in an effort to execute a "more financially disciplined" version of Pat's original foundry plan.

The updated mandate is focused first on survival, then profitability. Tan intends to incur additional sweeping layoffs, cutting the company's managerial layers by about 50%. The new focus is going to be on the upcoming 14A process node in close partnership with large external customers.

In theory, the IDM 2.0 plan directly addresses the fatal flaw of the first Intel Custom Foundry, where the process technology was designed for Intel products first. With major financial commitments coming in from Nvidia ($5 billion) and SoftBank ($2 billion), who owns ARM, there is at least some hope that Intel can revitalize its foundry business.

The open question is, will Intel learn to play well with others?